As my efforts to be greener and all natural in the shop have evolved,

I've naturally been more interested in hand tools. You just have to take

a quick spin through the handful of posts that precede this one to see

that. Hand planes do some things that other tools just can't do, and

they do some things better than the alternatives. Even some power tools

don't stand up to what can be done with a hand plane. That being said,

there are also some limitations that need to be considered. In this

post, I'm going to walk you through how I cleaned up an older plane I

bought for jointing,* while also touching on what I see as the

benefits--and the limitations--of hand planes.

First off, there are lots of different types of hand planes, from

general purpose smoothing planes like the Nos. 4 & 5, to specialty

planes like routers and rabbet planes, to wooden shaping planes; Stanley

alone has over 200 planes in their (historic) catalog. Want to know more, go see

Patrick Leach.

The Stanley No. 5, or jack plane, is a general purpose bench plane, but has a long

enough bed for jointing in a pinch. The 5 I've fixed up is a

cast iron bodied plane

with rosewood handles (tote and knob) a heavy steel blade and chip

breaker assembly and an adjustable steel frog, fitted with a brass and plastic knob

to set the cutting depth and a lateral adjusting lever to adjust the squareness of the blade

against the bed of the plane. All of this adjustability hardware means that the cast iron bodied smoothing plane can be tuned and adjusted on the fly without tapping on the cutting iron, wedge or plane body with an adjustment hammer as you would on a simpler wooden version.**

The adjustablity that is built into the Stanley-type bench plane, means that the plane can be broken down to its basic parts. This really helps when it comes to cleaning. Once the plane is broken down, the parts fall into three major groups: The plane body, the rest of the metallic parts, and the wooden knob and tote. The cleaning methods I used on the plane body and the rest of the metallic parts is similar, but the size of the body, and the flatness of the working surfaces, make it a little different than the other parts. The wood parts clearly need a different kind of a attention.

Once its apart, I dust everything off and set the wood parts aside. Next, I take each of the metallic parts to the sink and wash them with scouring powder and really hot water. I know, rust. The hot water brings the temperature of the piece up to a pretty toasty temperature. I wash and rinse them one at a time, and then dry them while they are still hot. I knock or blow the water out of the screw holes and the heat in the metal evaporates off the rest in no time. Take care cleaning the blade, its easy to cut yourself.

Next, I chip off the paint drops--why are there always drips of paint on old tools?--being careful not to damage the Japanning. For this I usually use a sharp piece of hardwood, like maple, rather than a metal tool. After that, I check for rust. Fine surface rust comes off easily enough with some steel wool, or fine sandpaper. For the flat parts of the plane, I'm careful to clean them on a flat surface, coated with sandpaper, to make sure the surfaces stay flat. For bad rust, I drop the parts into some white vinegar overnight, and then its back to sink for more scouring powder and hot water. After the heavy rust is removed, I clean them parts as noted above. A wire brush is handy for hard-to-reach places, but I don't use it on the Japanned areas, or the brass/plastic bits.

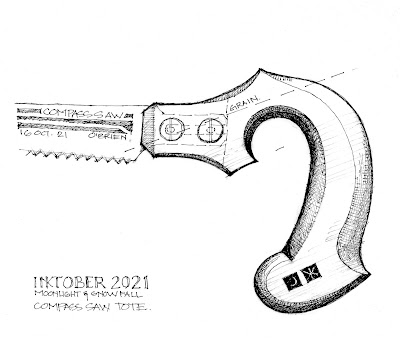

The wooden tote and knob usually clean up nice with a little steel wool and some paste wax, but if you've got a broken tote (and it happens, boy) then you've got a more serious problem on your hands. I've done some

tote repairs on planes and saws in the past. Getting the original shape right can be the tricky part. Luckily, this plane didn't have any damage to the wooden bits.

Once everything is clean and rust free, I put on a coat of paste wax before I put it back together. A little light oil goes in the screw holes and on the threads of the screws. I pay special attention to the paste wax on the raw metal parts such as the face and the cheeks of the plane, the blade, and chip breaker, and the lever cap, as it really helps to keep the rust at bay.

* I've since picked up a Union No. 7 jointer plane at a yard sale for

just a few dollars. It's in pretty bad shape, but I'm going to see if I

can tune it up and get it working.

** Stanley (and others) also make wooden planes with metallic inserts (often referred to as

transitional planes) that allow a lot of the same adjustability as their metallic counterparts. I'm comparing metallic planes to the traditional wood plane with a wood wedge holding the iron in place against a bed that's carved right into the body of the plane.